Sex, Drugs and Rock and Roll Part III: Rock and Roll by Stevie Adamek

Posted on February 26, 2014This is the last installment of a three-part series on what I learned touring with Journey, Boston and Van Halen as part of the melodic rock band, Bighorn, in the late 70s. As I mentioned in Part II (Drugs and Alcohol), rock and roll – actually any kind of music – is a business. Rock and roll touring is a special kind of business, though.

These days, of course, there are no more record stores, a lot of promotion is done through social media, and almost everyone downloads and listens to music on their phones. Some things are still pretty much the same in the music business – there’s still a lot of sex and drugs. It’s also still all about the money. For us artists, though, it’s always going to be about the rock and roll.

Here are some of the most important things I learned as a touring musician:

Take Opportunities When They Appear And Don’t Look Back

Bighorn had been together for 7 years before I joined the band. They were the top nightclub act in the Seattle area – mostly a cover band (Zeppelin, Queen, Stix, Yes) with a few originals thrown in. In August 1977, their management decided that they needed someone with a proven record of writing original songs to move them forward.

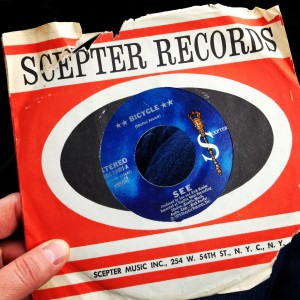

Peter Davis, the keyboard player from Bighorn, had a solo career going as well. I had met him at Seattle West Studios (Sea West), where he had hired me as a studio musician to play drums on his solo record (I was also an engineer there). This was 1977, the same time Heart was recording their fourth album, Dog and Butterfly, in the room across the hall at SeaWest. In addition to engineering at SeaWest, I was playing and writing music in a four-person band called the See Band. I was 26 at the time.

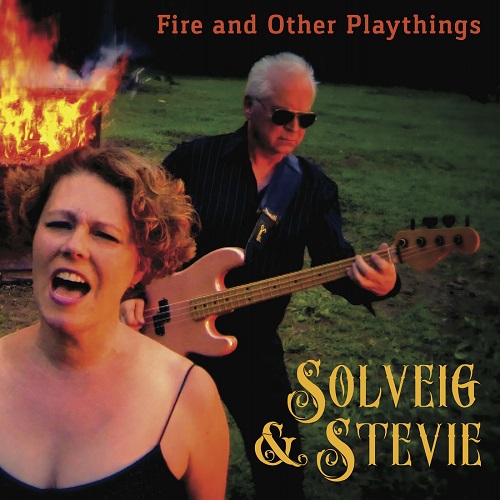

When Peter was approached by Scott Soules, Bighorn’s manager, to play keyboards for them, he recommended I come with him and join Bighorn on drums. Scott liked the idea, because I was more than a drummer: I had proven that I could write original songs. I had written several songs for the See Band, one of which, Bicycle, been recorded and released as a 45 by New York label Scepter Records (Dionne Warwick, The Kingsmen, The Shirelles, The Guess Who, Burt Bacharach). Scepter had signed us and funded the recording of Bicycle at SeaWest, and the owner of SeaWest, Rick Keefer, and I had produced it. Scepter was founded in 1959 by Florence Greenberg, but Florence had retired in 1976, and sold the catalog to Springboard International.

When Peter was approached by Scott Soules, Bighorn’s manager, to play keyboards for them, he recommended I come with him and join Bighorn on drums. Scott liked the idea, because I was more than a drummer: I had proven that I could write original songs. I had written several songs for the See Band, one of which, Bicycle, been recorded and released as a 45 by New York label Scepter Records (Dionne Warwick, The Kingsmen, The Shirelles, The Guess Who, Burt Bacharach). Scepter had signed us and funded the recording of Bicycle at SeaWest, and the owner of SeaWest, Rick Keefer, and I had produced it. Scepter was founded in 1959 by Florence Greenberg, but Florence had retired in 1976, and sold the catalog to Springboard International.

The See Band’s main claim to fame was that we had opened up in 1975 for Sugarloaf, who had the hit song Green Eyed Lady. We opened for Sugarloaf at the 1,500-seat historic art deco Capitol Theater in downtown Yakima, WA, which actually burned down the very night after we played there (it was subsequently rebuilt). I was working fulltime, producing already at SeaWest Studios, though, so really the See Band wasn’t a touring band. We hadn’t toured anywhere outside the Seattle area.

The See Band’s main claim to fame was that we had opened up in 1975 for Sugarloaf, who had the hit song Green Eyed Lady. We opened for Sugarloaf at the 1,500-seat historic art deco Capitol Theater in downtown Yakima, WA, which actually burned down the very night after we played there (it was subsequently rebuilt). I was working fulltime, producing already at SeaWest Studios, though, so really the See Band wasn’t a touring band. We hadn’t toured anywhere outside the Seattle area.

Also, we only had a singles contract with Scepter. They had released Bicycle regionally, and it had gone to number two in Yakima, WA, number 8 in Eugene, OR, and was in the top ten in Aberdeen, WA. A promoter had put us on tour with the Stones’ Gimme Shelter movie, and we went down I-5 playing theaters right after they showed the Stones movie. We were two years into it, though, and it wasn’t really going anywhere, probably because the label by then had fallen apart and been split in pieces.

The Bighorn opportunity was much bigger, so I folded the See Band and went on to Bighorn. I’m still good friends with Charlie Morgan, lead guitar. The See Band’s bass player and backup singer was Joe Chemay , who went on to play with Fiona Apple and many other artists.

Signing with Bighorn turned out to be a good move, because just after I joined, Columbia Records/CBS (US and Canada) signed the band. In November 1977 we headed up to Vancouver, BC, to record our first album at Little Mountain Sound Studios (Loverboy, Aerosmith, Metallica) with British producer Martin Shaer (Nick Gilder/Hot Child In The City, Sweeney Todd). From there, things started to take off, as the label started booking us out to open for national acts.

Opening for Bigger Bands Is Not Where the Money Is

Bighorn made $3500 a show for opening up for one of the national acts. That would have to cover the cost of being on the road (transportation, rooms, food, roadies), as well as about $450 a week in a band “salary” for each of us in the band ($2400 total for the whole band). Our label didn’t get paid for the performances. Our manager would handle collecting the performance fees, he would take his cut, and then he’d pay out the rest for the costs of the tour. He was both band manager and road manager. The truth was that, at best, opening for a big act was break even.

Where we actually made money was playing the off nights, like Tuesday through Thursday/Friday. If Scott could book us into a nightclub nearby the concert hall, we could make another $5000 playing 4 nights of the same week. There were booking agents who dealt specifically with these clubs, and Scott knew these guys who could find us a place that would hold 1200 or 1300 people so we could pack the place.

At that time, there were no blackout requirements, so we could play as many nights at the same club leading up to or following the bigger shows. All those smaller shows pointed to the big show, so it was a win-win, no one was worried about cannibalizing the audience. In those days, tickets were priced so that fans could afford to go see a band multiple nights in a week – and many did! Some fans would see us every single night we were playing.

Nothing Beats Small Towns For Excitement

With Bighorn, we opened for the bigger national bands like Van Halen, Journey and Boston for 4-5 dates in Seattle, Hawaii, Montana, North Dakota, and Idaho. It was a win for them, because we had the local fan base they could tap to increase draw, and it was great for us (although as I said, we barely broke even on expenses). But it sure was fun.

When we played in Montana or North Dakota, the arena would have a nearby Holiday Inn, and we would all be staying there – both bands in the same hotel. Sometimes, there were kids already camped out in the hotel hallways when we arrived, especially in the Midwest, where rock shows are real destination events.

When we played in Montana or North Dakota, the arena would have a nearby Holiday Inn, and we would all be staying there – both bands in the same hotel. Sometimes, there were kids already camped out in the hotel hallways when we arrived, especially in the Midwest, where rock shows are real destination events.

In the Midwest and in the smaller towns, the fans were really focused. Going to our show was one of the biggest things they would be doing that whole year. The energy was much more intense, and the audience enthusiasm during the performance was much higher. It’s subtle, but it’s definitely different. There were always more people who wanted autographs at the end of the show. A smalltown promoter was more open to having more fans hanging around waiting for autographs, too. In bigger cities like Seattle, they would all be shooed away by security.

The fans weren’t jaded either, because they didn’t have nearly the same number of shows to choose from as in the bigger cities. They were very “creative” in expressing their gratitude to us. You can read more about that in Parts I and II of this series. Let’s just say, the excitement level and fan interaction was higher in smaller towns. Overall, I think we made more money, sold more records, and had a lot more fun in smaller towns than we did in the big cities.

The Point Is To Sell Records, So Coordinate Your Touring With Marketing Promotion

Bighorn ended up opening for these big national bands because we were signed with CBS. They had a promotions department who worked with Scott, our manager, to find cities where our record would already be stocked in the record stores. CBS would try and get a couple of tracks on the radio while we were there. That’s called “tour support” – basically they paid the radio stations to play us, and would ship our records out to the stores ahead of the tour dates so it was available around the time of the shows.

The labels “helped” with (ie. paid for) this tour support (radio station play), but they only had a certain amount of money. Scott and his mom also invested a lot of money in Bighorn over the years. As I mentioned above, we made extra money in places where we could play at a local club (which the label didn’t get a cut of), and the label had given us an advance. The point of the tour, though, and the reason the label paid for “tour support” was that we sold a lot of records whenever we played a bunch of shows. We had to pay back our advance back out of those record sales (or our percentage of them), however.

Bighorn’s advance when we were signed was $90,000 (total for the band), and I got an additional $1500 advance as a writer. Out of that, we spent about $50K on the record for the studio time and to pay Martin Shaer, the producer. We also made the weekly salary I mentioned of $450 each, which came out of a combination of the show proceeds and record sales. We got checks for maybe $20 or ten cents here and there for the airplay, but all the money from record sales went back toward paying for the advance. I have one of my licensing check receipts from Columbia still, I think it’s for three cents.

Breaking Out Of The Regional Rut (Or Not) And The Demise of Bighorn

The Bighorn record bubbled up in Texas and Toronto, and we had more than a few FM stations in the region playing it. We were hoping CBS could get product shipped out and in the stores to coordinate with tour dates, and we wanted to figure out if there was anyone big who was going out on tour who we could open for, or enough nightclubs to make money to make it worthwhile.

In Texas, though, there were no big clubs we could work with, and it was so far away – getting there was expensive. We also ended up in a difficult place where there were some problems between CBS America and Canada. Our manager, Scott, was telling us that the two label divisions were unable to agree on the tour strategy, and that was very frustrating. The argument was: if we played in New York why couldn’t we coordinate that with our Toronto tour dates, and if we played in Alberta, could we coordinate with Minnesota or North Dakota? It seemed each division wanted priority and they couldn’t work together to make the tour cost-effective for us in terms of travel schedule.

At some point CBS America called our manager and told him the record was dead. Our only choice at that point, before they called it dead, would have been to bring in our own money to tour more in cities where we could get airplay and get records in there and sell more. It was very competitive, though, because each market had their own bands just like ours (big hair melodic rock) who had also just signed with a label and were trying to promote themselves.

At that point, CBS told us they wanted us to record another record. We felt that New Wave was in and big hair melodic rock was out, and it didn’t make any sense to get committed to making another record. At that point, the band decided to decline the offer to make another record with CBS. We were released from our contract, and decided to go on and form the Allies out of Bighorn, with new music and a new record. Scott’s Mom funded the recording of the Allies, and we signed to Victoria Records and went on to some regional success (again), but never signed to a larger label.

You Gotta Ride It

Rock and roll is a fickle maiden. You have to ride her while she’s hot, and take the ups and downs with grace.

One of the best things about being in these bands was that I developed great relationships that have lasted a lifetime and brought me much joy (and continued business) over the years. After all, what really matters is working with people you love and respect, and creating something you can look back on with pride.

I feel fortunate to have collaborated with so many great musicians and producers over the years. Although today I have less hair, I have much more wisdom.

Touring in a rock and roll band was the experience of a lifetime.